Food Rules

Our world must be truly mad that we need a book like this, and yet we do. Though I just stumbled across it the other day, Food Rules by Michael Pollan, illustrated by Maira Kalman, is four years old, published in 2011. It’s lost none of its bite or relevancy. Pollan is the journalist author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, a pioneering look at what we eat and where it comes from, and Maira Kalman is a New Yorker illustrator who has invented her own humorous style of thinking out loud with pictures. Together they bring warmth and humanity back to the food table with a handful of simple rules.

Our world must be truly mad that we need a book like this, and yet we do. Though I just stumbled across it the other day, Food Rules by Michael Pollan, illustrated by Maira Kalman, is four years old, published in 2011. It’s lost none of its bite or relevancy. Pollan is the journalist author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, a pioneering look at what we eat and where it comes from, and Maira Kalman is a New Yorker illustrator who has invented her own humorous style of thinking out loud with pictures. Together they bring warmth and humanity back to the food table with a handful of simple rules.

The book asks how food ever got so complicated, so misleading, so contentious? It finds common ground not in pseudo-scientific jargon but in family wisdom and challenging quips. Here are a few samples: Rule 6: “Avoid food products with more than five ingredients.” Rule 13: “Shop the peripheries of the supermarket and stay out of the middle.” Rule 16: “Go food shopping every week.” Rule 22: “It’s not food if it arrived through the window of your car.” Rule 25: “Eat mostly plants, especially leaves.” Rule 28: “Eat your colours.” Rule 45: “Eat all the junk food you want as long as you cook it yourself.” Rule 53: “Pay more, eat less.” Rule 65: “Give some thought to where food comes from.” Rule 75: “No labels on the table.”

While I’m reading this delightful little book, my wife returns home from a “Food Nutrition Education Party,” organized by a friend of a friend. It used to be tupperware parties, than stretch-wear parties, now it’s food education parties. Those attending the event were grappling with feeding their families in the midst of launching careers, tight budgets, busy schedules, and baffling conflicts of information.

I’m reminded of how I come home from meetings at the Ecology Action Centre, frustrated that no one in the room can agree on anything to do with food. Kathleen answers: you know about the latest theories of change, don’t you? You’ve heard of chaos theory? Two people adjust their diets and this has an unexpected effect somewhere else–an organic farmer is able to expand his business, say. A hundred thousand small changes each trigger further changes. None of this can be plotted or predicted. But the cumulative effect is powerful and creates a entirely new way of thinking and doing things.

Pollan and Kalman are among the friendly but chaotic non-plotting agents of change. I sense something changing the minute Pollan asks: “What is going on deep inside the soul of a carrot that makes it so good for us?” Or again when he notes how “seventeen thousand new products show up in the supermarket each year, all vying for your food dollar. But most of these items don’t deserve to be called food–I prefer to call them edible foodlike substances. They’re highly processed concoctions designed by food scientists, consisting mostly of ingredients derived from corn and soy that no normal person keeps in the pantry, and they contain chemical additives with which the human body has not been long acquainted. Today much of the challenge of eating well comes down to choosing real food and avoiding these industrial novelties.” The book advises the reader to avoid traps set by clever marketers and to rely on simple undisguised whole foods. More than this, to follow a sensible and disciplined approach toward food to enhance quality of life through better health. In the process, a new invigorated food culture emerges.

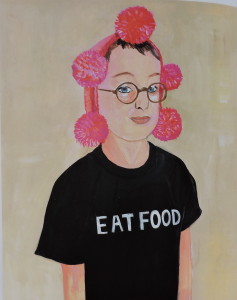

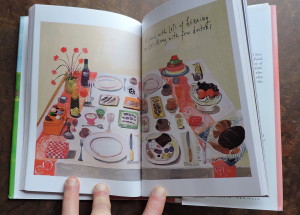

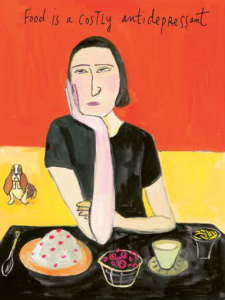

Maira Kalman’s illustrations are worth noting. Colourful, painterly, charming, full of wit and attention to detail by an artist who is curious about other people. I especially like the picture of the Eat More Grocery Store with isles labled “despair,” “anxiety,” “sadness” and “anger.” If you like this artist, you might enjoy the personal and idiosyncratic flow of Kalman’s TED talk.

Maira Kalman’s illustrations are worth noting. Colourful, painterly, charming, full of wit and attention to detail by an artist who is curious about other people. I especially like the picture of the Eat More Grocery Store with isles labled “despair,” “anxiety,” “sadness” and “anger.” If you like this artist, you might enjoy the personal and idiosyncratic flow of Kalman’s TED talk.