One reason why our environmental problems are so vexing and polarizing is because they are largely self-inflicted. We are the problem. We enjoy the benefits of burning fossil fuels, just as we enjoy the low costs of food that come from industrial farming. However unsafe energy and agriculture practices are causing serious long-term damage, the cost of which is unaccounted for. The good news is: we are also the solution. We can work together to invent new strategies to safeguard the environment while maintaining current levels of productivity. These strategies involve recognizing shifts in a business landscape.

One reason why our environmental problems are so vexing and polarizing is because they are largely self-inflicted. We are the problem. We enjoy the benefits of burning fossil fuels, just as we enjoy the low costs of food that come from industrial farming. However unsafe energy and agriculture practices are causing serious long-term damage, the cost of which is unaccounted for. The good news is: we are also the solution. We can work together to invent new strategies to safeguard the environment while maintaining current levels of productivity. These strategies involve recognizing shifts in a business landscape.

A shifting landscape creates opportunities as well as problems. We need to distinguish two different kinds of solutions to problems. Some solutions solve an immediate problem, but they lead to further problems. Often these further problems are more serious than the original problem. Here’s an example: In the 19th and 20th centuries, people burned coal and other fossil fuels in furnaces, cars and other machines. This solution worked for a time. It solved the one problem of running our machines and supplying power to our cities. However, this solution led to more serious subsequent problems: pollution, climate change, and the acidification of our oceans. A small problem mushroomed into a gigantic problem.

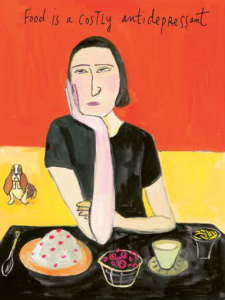

Here’s another example: as our population increases, there is an increased demand for food. The problem is our farmland is limited in size. The short-term solution has been to increase the use of fertilizers and pesticides and at the same time to alter the genes of our favourite plants to make them more resistant to these toxins. This has made farms more productive, with higher yields per acre. Unfortunately this solution has led to more serious subsequent problems: the toxins used on our foods and the genetic modifications have led to an increase in autism, diabetes, heart disease, cancer and dementia. In short, we have more food now than before, but the food we have is making us sick. On top of this, the way we’re growing our food is depleting the natural nutrients in the soil and turning farmlands into deserts.

The kind of solution that solves one problem but leads to a more serious problem needs a name. I call it a “net-loss solution.” In contrast, a solution that brings positive long-term benefits might be regarded as a “net-gain solution.” I borrow these terms from the language of accounting. If we are to survive our own self-inflicted problems, we need to encourage or reward those who choose net-gain solutions, while discouraging or punishing those who choose net-loss solutions that threaten the well-being of our communities.

One of our greatest problems is this: we make organizations that operate with net-loss solutions into fortress-like institutions and mighty industries, as if they were essential to our collective identity and sense of self-worth. Blunders made by these entities are dressed up to appear respectable. To reform a destructive practice is regarded as an impossible proposition, an assault on culture itself.

Why is it impossible? These entities are businesses that must respond like any business to the changes taking place around them.

The New Energy Model, the New Farming Model

People resist change because it’s hard to imagine what the new order will look like, how it will work, how it will affect our jobs, our lives, our families. That’s why we turn to models—conceptual tools that structure the way groups operate and interact. One model that has recently impacted all our lives is the “producer/ sharer” model. This is the model behind mobile technology. The old model in communications allowed a handful of TV stations and newspapers to produce all the content and information for the bulk of the population to passively consume. This was a “producer/ consumer” model. Information only flowed in one direction, from a central TV station or big city newspaper office to households around the country. The average person made little contribution. The Internet has made this model obsolete. Of course there are still TV stations and newspapers, but they now one source of information among many. Today, TV stations and newspapers are like tiny rivers flowing into a vast reservoir of information into which everyone posts stories and shares information. We are all producers of news and information, as well as being sharers. We are active participants.

This “producer/ sharer” model is currently shifting the landscape in two other fields: energy and agriculture. As home owners install more and more solar panels, heat pumps and other forms of new energy technology, sending excess power back to the grid, and drawing energy when it’s needed, they become producers of energy as well as sharers of energy. The clean energy technology saves homeowners and businesses money, it helps the environment, but most important, it changes the landscape and the model of industry.

This “producer/ sharer” model is currently shifting the landscape in two other fields: energy and agriculture. As home owners install more and more solar panels, heat pumps and other forms of new energy technology, sending excess power back to the grid, and drawing energy when it’s needed, they become producers of energy as well as sharers of energy. The clean energy technology saves homeowners and businesses money, it helps the environment, but most important, it changes the landscape and the model of industry.

Community gardens and urban farms are also helping people become producers and sharers of food. People dislike the notion of one giant corporate farm feeding the world and feeding it badly. The model is top-heavy and doesn’t work. We want more control over what we eat. We want healthy food that hasn’t been modified in labs and sprayed repeatedly with cancer-producing toxins. The only way to do this is to get involved and grow some of the food ourselves, to grow it locally, and when we can’t do it ourselves, to support those small-scale local farmers who do.

Once the new producer/ sharer model is accepted, as it was in the field of communications, there is no turning back. Our cell phones, Internet, and social media accounts have become indispensible tools that factor seamlessly into our everyday routines.

I like to think that the revolution in social media is only “Part 1” of a larger transformation, a transformation with a powerful underlying purpose. That purpose is to give people the tools to rally and work together at a moment of environmental crisis. We won’t heal the world by talking to each other on our phones. That’s not the tool I’m talking about. The tool I have in mind is a template of interaction that can extend beyond communications to other fields such as energy and food production. This is the producer/ sharer model. In the field of energy it means building a network of local power producers. This might take different forms, such as enabling a million homeowners and small businesses to place solar panels on their roofs. If a network of cell-phone towers can be constructed around the country, why couldn’t a network of solar towers also be constructed? In the same way, it doesn’t take too much imagination to picture individuals planting food gardens in spaces that used to be lawns or vacant lots around the country.

No one’s permission is required. It just needs a million people with the willpower to make it happen. The movement has already started. The early adapters enjoy cheap clean power and healthy food. Others are following because they see that it makes sense not only for themselves but for their communities as well. The key to a producer/ sharer model is not to rely on a central power, whether that’s a giant corporation, a power utility, an industrial farm, or a government, to make things happen. People have to take it upon themselves to install their own solar panels and plant their own gardens and once they do, a meaningful social transformation takes the form of an unstoppable and inevitable movement.

As we enter uncharted waters, people are understandably fearful, reluctant to be the first one in. Tough decisions are always made in the face of fear. That’s what makes them tough decisions. But we can take confidence from the fact that our action plan is modeled after a movement in social media that has not only been successful, but also has allowed a degree of mobility and maneuverability that will be essential to us in the difficult times ahead.

Why I wrote this essay

Concepts are ideas in motion. We cannot change our destructive ways without changing conventional ways of thinking. People need to act with confidence and strong sense of purpose. To do this, we need ideas and core principles upon which to build a unified front. In this essay, I offer a few concepts to help clarify common goals and strategies. I start with the notion that a “tough decision,” is triggered by a “change in a business landscape.” When landscapes shift, both problems and opportunities arise. I argue that “net-gain solutions” are preferable to “net-loss solutions.” I also put forward the concept of a “producer/ sharer model” in contrast to a “producer/ consumer model.” Social media uses a producer/sharer model to great effect. The same model could be applied to the fields of energy and agriculture with similar success.

A day after writing this, I received an email from a friend who is a member of Citizens Climate Lobby Canada (CCLC). This group has been meeting with politicians in Ottawa to work out the perimeters for a national carbon tax, patterned loosely after the carbon tax successfully introduced in British Columbia in 2008. A national carbon tax is a good idea, but it has one flaw. It punishes those who practice net-loss solutions, but it doe not reward those who practice net-gain solutions. In the CCLC proposal, those who use carbon-emitting machines are taxed. The tax is earmarked as “revenue-neutral” with all money collected being redistributed back to Canadian tax-payers. The idea is to benefit low-income groups, who use less carbon-emitting machines than high-income groups. In essence, the low-income groups are given an energy rebate. As the rebate is spent on disposal items, the money gets rechanneled back into the economy, providing a boost for retailers and small businesses. Everyone seems to win.

The problem with this is it does not change the model of industry. It does nothing to build a new de-centralized infrastructure nor does it mobilize the money and resources that are needed for new clean technology. The carbon-emitters simply pass on their increased costs by charging higher fees. Higher fees may eventually create consumer resistance that in time could lead to people seeking other alternatives. We need more direct action.

Let me give a parallel case. Food production is as big a problem as energy and the way we address the one problem will illuminate the way we address the other. In Canada and the United States, food plants, such as wheat, corn and potatoes, are genetically modified to allow greater exposure to toxins. Both the genetic modifications and the toxins that get into our food are harmful to human health. The food keeps us alive, but over time it causes severe health problems. We can kid ourselves and say, having cancer or diabetes or dementia is just the price we have to pay to feed ourselves. This is insanity.

If you had told someone 50 years ago that smoking cigarettes causes cancer and that a cigarette tax would be funnelled back into a rapidly expanding healthcare system to offset the increased cases of cancer, people would have said: 1) cigarettes do not cause cancer and 2) you can’t tax a product so many people use because people won’t stand for it, nor will the companies that make tobacco, nor will governments. Today, the cigarette tax is unquestioned. How is the cigarette tax different from the proposed toxic food tax? Cigarettes are luxury items that people can live without. Food is not a luxury item. The purpose of the “toxic food tax” is not to punish self-indulgent people, as we do with the cigarette tax, but to prevent an industry from becoming toxic-food-only. The tax allows consumers an option of buying non-toxic food.

If you had told someone 50 years ago that smoking cigarettes causes cancer and that a cigarette tax would be funnelled back into a rapidly expanding healthcare system to offset the increased cases of cancer, people would have said: 1) cigarettes do not cause cancer and 2) you can’t tax a product so many people use because people won’t stand for it, nor will the companies that make tobacco, nor will governments. Today, the cigarette tax is unquestioned. How is the cigarette tax different from the proposed toxic food tax? Cigarettes are luxury items that people can live without. Food is not a luxury item. The purpose of the “toxic food tax” is not to punish self-indulgent people, as we do with the cigarette tax, but to prevent an industry from becoming toxic-food-only. The tax allows consumers an option of buying non-toxic food.

Foods that cause cancer and other illnesses are a net-loss problem. Industrial farmers who grow such foods need to be discouraged or taxed. This tax money needs to be redistributed to organic farmers who are willing to grow foods that do not present risks to people’s health. In this way, the tax has a double benefit. It both punishes and rewards, while financing a new model of production that’s healthier for the environment and for people.

It’s the same with energy. The carbon tax punishes the users of old energy technology with their net-loss solutions, and the money raised by the tax should be redirected to building a de-centralized system of energy producer/ sharers, using new clean energy technology with net-gain solutions.

I started this essay with the slogan: we are the problem, we are the solution. We cannot afford to isolate a few large players as scapegoats, when in truth, as consumers of energy produced by fossil fuels and as consumers of food produced by industrial farms, we are all to blame. We cannot give ourselves an energy rebate when we’ve done nothing in the way of changing habits to deserve it. We need an underlying principle, such as punishing net-loss solutions and rewarding net-gain solutions, and we need to be consistent in applying it. A practical response to a shift in a business landscape, is to wisely reinvest in a new infrastructure—such as using a producer/ sharer model– and the training of people in the technology used by this model. Just as we need a carbon tax, we need a Health Risk Food Tax. This tax money then needs to be directed back to small-scale localized producer/ sharers of clean energy and to small-scale localized producer/ sharers of organic food.

Governments act in response to movements and shifts in popular sentiment. The great thing about small-scale alternatives in energy and food production is that anyone can step in and be part of this transformative process. As the numbers of local producers increases, the movement will grow and become an inevitable force of positive change.

This weekend Solar Nova Scotia organized a tour of two passive solar homes in St Margaret’s Bay built by visionary designer, Don Roscoe. Though the weather was wet and miserable, about 20 members turned out to hear from Don and the gracious home-owners. The homes are stunningly beautiful and so warm we were all peeling sweaters. What the two houses had in common were two-storey cathedral windows on the south side, berms on the north side, a mezzanine level overlooking the open-concept design, and hidden air circulation systems. Both houses nestle naturally in with surrounding landscape.

This weekend Solar Nova Scotia organized a tour of two passive solar homes in St Margaret’s Bay built by visionary designer, Don Roscoe. Though the weather was wet and miserable, about 20 members turned out to hear from Don and the gracious home-owners. The homes are stunningly beautiful and so warm we were all peeling sweaters. What the two houses had in common were two-storey cathedral windows on the south side, berms on the north side, a mezzanine level overlooking the open-concept design, and hidden air circulation systems. Both houses nestle naturally in with surrounding landscape.

I was fortunate to be there filming as Nigel bolted the last panel in place. It was surprising to see how quickly–just a matter of minutes–it took to network the panels together and plug the system into an inverter. By noon, the house was running on its own supply of solar power. This project is the first of three started in the area by a group of neighbors, who ordered their panels together in bulk.

I was fortunate to be there filming as Nigel bolted the last panel in place. It was surprising to see how quickly–just a matter of minutes–it took to network the panels together and plug the system into an inverter. By noon, the house was running on its own supply of solar power. This project is the first of three started in the area by a group of neighbors, who ordered their panels together in bulk.