Vitamin D: Changing Attitudes to Medicine

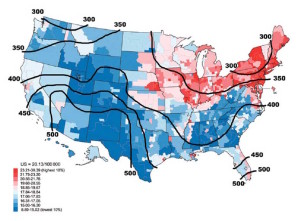

Nutrition is often treated as an after-thought by the public, by the media and by researchers who see medicine as a brave new world of wonder drugs, zappings, and other space-age procedures, played out in an arena of high technology. But this attitude may be changing. In his 2010 talk, Vitamin D: Role in Preventing Cancer, presented by the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, Dr. Cedric Garland makes a strong case for using Vitamin D as a primary means of cancer prevention. He starts his lecture by showing a map of the United States, colour-coded red to indicate the regions where breast cancer cases most commonly occur. He asks why cancer is more common in the northern latitudes of the industrial coal-burning Northeast and less common in the sunnier latitudes and less industrial regions of the country?

This map correlates breast cancer rates and the degree of sunlight with its strong natural vitamin D component.

Critics pooh pooh such stuff because it is epidemiological evidence, collected by analyzing associations between disease incidence and diet, environment, etc. This is only association, they say, it doesn’t prove causation. And they are right. The only absolutely rigorous proof is a double-blind placebo controlled study conducted with large numbers of people over a considerable period of time. Unfortunately, it is unlikely this is ever going to happen, because there’s no profit in it for the corporate interests. This kind of reasoning that rejects reasonable and helpful data because it is not definitive gives medical researchers (and the pharmaceutical body) a good excuse not to take any action in the direction of nutrition and environment. We don’t challenge the “experts” on this, bowing to their superior “knowledge and wisdom.” As a result, we find ourselves locked in a limbo state, where we generously fund “cancer research” to find the magical pharmaceutical silver bullet. The conveniently concealed knowledge is there is no such thing. The answer will never be found this way and thus there is a wonderful, endless source of funds and profit-taking from high priced drugs, which pretend to offer solutions, but don’t really.

The experts should be challenged. Although absolute causation cannot be proven, the circumstantial evidence is strong. So-called “primitive people,” living in places with lots of sun, and contemporary beach-patrolling lifeguards who have similar exposure to naturally-generated Vitamin D, have levels that fall between 50 and 80 nanograms per milliliter. In contrast, modern people who shun the sun, based on misguided fears of skin cancer, have levels drastically lower than that. Indoor lifestyles add to the problem, especially for those living in higher northern latitudes. The flu season clearly follows the winter low-sun time. In the southern hemisphere, the flu season is six months out of synchronism with the northern hemisphere, which is perfectly consistent with the “theory” that Vitamin D deficiency has an effect on immune systems.

The experts should be challenged. Although absolute causation cannot be proven, the circumstantial evidence is strong. So-called “primitive people,” living in places with lots of sun, and contemporary beach-patrolling lifeguards who have similar exposure to naturally-generated Vitamin D, have levels that fall between 50 and 80 nanograms per milliliter. In contrast, modern people who shun the sun, based on misguided fears of skin cancer, have levels drastically lower than that. Indoor lifestyles add to the problem, especially for those living in higher northern latitudes. The flu season clearly follows the winter low-sun time. In the southern hemisphere, the flu season is six months out of synchronism with the northern hemisphere, which is perfectly consistent with the “theory” that Vitamin D deficiency has an effect on immune systems.

Modern chronic diseases, rare in our hunter-gatherer ancestors, are now rampant in current populations. These chronic diseases consistently appear alongside lowering levels of Vitamin D in our blood, including a lower chance of cancer survival if diagnosed in the winter, rather than in the summer.

Popular fears that “high” Vitamin D3 use (above 2,000 IUs per day) is “dangerous” is a bunch of caplooey. This misrepresentation of D3 was caused by earlier use of Vitamin D2, which does have safety limits. D3 is altogether more effective than D2 and much safer. One of the surprises of Dr. Garland’s research was the discovery that the intake of D3 can be very safely taken up to levels of 10,000 per day, especially with the added precaution of taking K2 at the same time. The fact that I am vertical right now, and not dead, speaks volumes to that, on a personal note.

So, given there is a high likelihood that there is significant positive benefit to be had, implementation is cheap (pennies per day), and there are no negative side effects, then the position of the medical establishment, not to support and indeed encourage optimal Vitamin D levels in the general population, but especially as the first order of business when processing and treating a patient is untenable, and indeed negligent.

If I appear to criticize the medical establishment, it should be noted that many doctors are also speaking out and creating a lively debate on these matters. American author and educator Sayer Ji has created a forum for many of these voices. This forum may in time become a movement. Ji calls it “green medicine.” My blog today was inspired by new info posted by Sayer Ji about a late 2014 study that confirms a causal relationship between Vitamin D and positive treatments for breast cancer. The authors of this study state (a bit evasively and not clearly enough for my liking, but perhaps due to legal advice) that the present treatment protocol for breast cancer in many cases either makes the situation worse or actually precipitates the dreaded metastasis, totally against the medical precept of “do no harm.” Many breast “cancers” are groups of somewhat abnormal cells, but among these are cancer stem cells, which are resistant to radiation and/or chemo treatments. By employing such invasive therapies, the majority of the mild mass of the tumour is destroyed, but leaves the stem cells untouched. After treatments, these resistant stem cells congeal in much greater proportion and spread rapidly. The tumour becomes highly malignant, leading to the death of the patient in short order. Whereas, if it had been left undisturbed, the condition may not have developed or would have done so much more slowly. The authors argue that getting sufficient Vitamin D to the patient may enable the body to clear the problem altogether.

Indeed, by encouraging the general population to take regular meaningful intake of nutrients such as Vitamin D3 as a matter of course, patients may be capable of dealing with errant cells at the first sign of cells going off track, and thus preventing any incident whatsoever. Indeed the almost total absence of all cancers in “primitive” or traditional peoples proves that optimally nourished humans are fully capable of dealing with wayward cells as they occur. I think this preventive nutrition-oriented approach is really the best scenario, and the one that I would favour promoting in our public health strategy.

Let’s try a test

When I use the term optimally nourished, I hesitate to restrict this just to the use of Vitamin D. Vitamin D works best as a co-factor with other nutrients such as magnesium, Vitamin K2 and Vitamin A. I would like to see a representative slice of the general population treated with optimal nourishment. What if half a dozen doctors, across the province, offered to supply patients with Vitamin D, etc. and then regularly measured their nutrient levels, with steps taken to “optimize” levels, as needed? These nutrition-supported patients would be monitored for how many and what kind of medical events they have for at least a couple of years, but ideally for many years. They could then be compared, on an ongoing basis, to the rest of the provincial population, and a reckoning of the cost savings (I am pretty confident there would be savings) produced from time to time, to prove the financial advantage, without even having to deal with the less clearly defined “quality of life” advantage. I think a study of this kind could be fairly low cost, and worth while. So, without dealing with the thorny issue of proving absolute causation, proving financial advantage is all it would take to make a very compelling case.